The CBOE Volatility Index (VIX) came on the scene in the 1990s as a way for investors to track expected risk in the market going forward. The Chicago Board Options Exchange’s VIX does something unique in that it uses 30-day options on the S&P 500 Index to gage traders’ expectations for volatility. In essence, it gives us a forward estimate of what the market thinks volatility in equities is going to be.

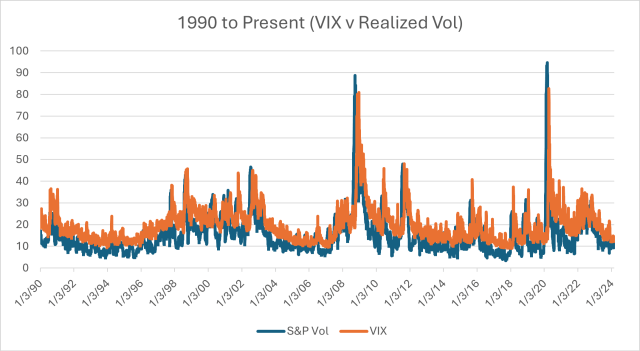

But how accurate is this measure on a realized basis, and when does it diverge from the market? We tackled this question by comparing the full spectrum of VIX data going back to 1990 to the realized volatility of the S&P 500 Index. We found that, on average, the market overestimated volatility by about 4 percentage points. But there were unique times when there were significant misestimations by the market. We tell this story in a series of exhibits.

Exhibit 1 is an image of the full-time series of data. It shows that, on average, the VIX overshot realized volatility consistently over time. And the spread was consistent as well, except for during spike periods (times when markets go haywire).

Exhibit 1.

In Exhibit 2, we summarize the data. The average S&P 500 Index realized volatility on a 30-day forward basis was 15.50% over the 35-year period. The average VIX (30-day forward estimate) was 19.59% over the same period. There is a 4.09% spread between the two measures. This implies that there is an insurance premium of 4.09 percentage points on expected volatility to be insulated from it, on average.

Exhibit 2.

| Average (%) | Median (%) | |

| S&P Volatility (forward 30 days) | 15.50427047 | 13.12150282 |

| VIX (30-day Estimate) | 19.59102883 | 17.77 |

| Difference (Actual Vs Estimate) | -4.086758363 | -4.648497179 |

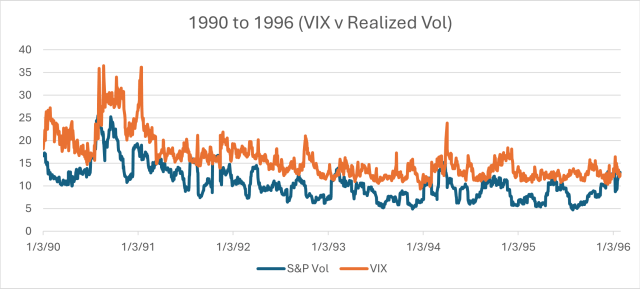

Next, we turn toward a time when no major crisis happened: from 1990 to 1996. Exhibit 3 highlights how markets worked during these normal times. The VIX consistently overshot realized volatility by approximately five to seven percentage points.

Exhibit 3.

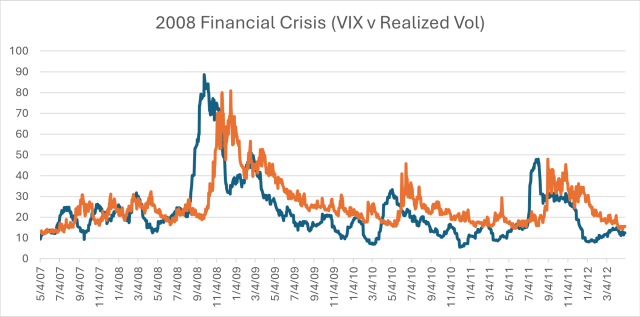

Exhibit 4 depicts a very different period: the 2008 global financial crisis (GFC), and we can see a very different story. In July 2008, realized volatility on a 30-day, forward-looking basis began to spike over the VIX. This continued until November 2008 when the VIX finally caught up and matched realized volatility. But then realized volatility fell back down and the VIX continued to climb, overshooting realized volatility in early 2009.

Exhibit 4.

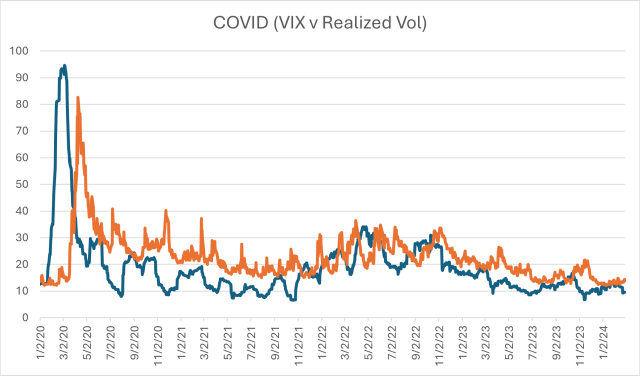

This appears to be a standard pattern in panics. VIX is slow to react to the oncoming volatility, and then overreacts once it realizes the volatility that is coming. This also says something about our markets: The Federal Reserve and other entities step in to quell the VIX once things look too risky going forward, thereby reducing realized volatility. In Exhibit 5, we saw this dynamic again during the COVID period.

Exhibit 5.

The Exhibits yield two interesting takeaways. One, investors, on average, are paying a 4% premium to be protected from volatility (i.e. the difference between the VIX and realized volatility). Two, the market is consistent in this premium; is slow to initially react to large, unexpected events like the GFC and COVID; and then overreacts.

For those that are using VIX futures or other derivatives to protect against catastrophic events, these results highlight how much of a premium you can expect to pay for tail risk insurance as well as the risk you take in overpaying during times of market panic.

Disclaimer: Please note that the content of this site should not be construed as investment advice, nor do the opinions expressed necessarily reflect the views of CFA Institute.

Original Post

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.

Read the full article here