Unlock the US Election Countdown newsletter for free

The stories that matter on money and politics in the race for the White House

The writer is an FT contributing editor and writes the Chartbook newsletter

The attack line from the Republicans is predictable: Kamala Harris was Biden’s border tsar. The crisis on the border with Mexico shows that she failed. So too is the response from the Democrats: No, the vice-president never was in charge of the border. Her role was to address the root causes of migration from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras. No one can blame her for failing. It was mission impossible.

The striking thing about this retort is not that it is unreasonable, but that it sets such a low bar. Whereas for the Republicans the desperation in Central America is reason to seal the border even more firmly, for the Democrats the deep-seated nature of those problems is an excuse. Apparently, no one expects Harris or anyone else to succeed in addressing the poverty and insecurity in the region. Shrugging its shoulders, the US settles down to live with polycrisis on its doorstep.

This isn’t to say that better policy comes easily. The problems hampering development in Latin America, the Caribbean and Central America run deep. The region contends with profound inequality, institutional failure, corruption, organised crime and poor educational and public health standards. All this in fragile commodity-centred economies that are exposed to climate change.

But then again, the aim is not to achieve complete convergence. A serious effort to address “root causes” would seek merely to lift the poorer sections of society out of absolute misery. When America’s political class shrugs its shoulders, what they are giving up on is the possibility of even this modest level of progress.

It doesn’t help, of course, that American affluence is both unattainable and part of the problem. It is the US that provides the market for the drug smugglers. It is Washington’s grotesque failure to regulate even military-grade assault rifles that supplies the weaponry. US sanctions against Cuba and Venezuela exacerbate tension without offering real off-ramps.

And fundamentally, there is deep policy fatigue. Everyone in the US knows that it would take a significant political effort to persuade Congress to appropriate serious money for Latin American development.

Harris’s “root causes” strategy was backed by $4bn over four years. To address the scale of problems in Central America, let alone Venezuela, that is peanuts. Following the blended-finance recipe, Harris multiplied those public funds with $5.2bn in private investment focused on manufacturing, internet and women’s empowerment. This is all to the good. But private investment is a slow-acting mechanism for addressing acute social and economic crises.

Trump slashed aid spending in the region. Biden did restore it, but to levels at half in real terms what the US spent in Latin America and the Caribbean in the 1960s. And that does not allow for GDP growth in the interim.

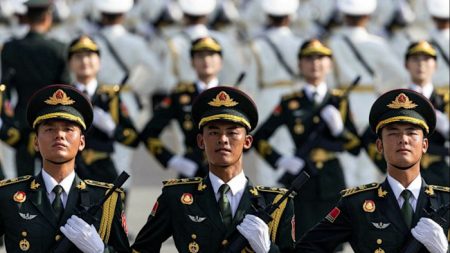

Of course, much cold war spending was disastrous: feeding military regimes and stoking political violence. But at least, at the time, the US perceived itself to have an existential interest in the region. Nowadays, competition with China occasionally raises a flicker of interest but that is at its hottest in the big economies of South America, a long way away from the crisis in the isthmus countries.

Images of caged migrant children raise a moral panic. But without the broader historical framing of the cold war and early 20th-century visions of pan-Americanism, what is left is a more or less cynical acceptance of the status quo. Unauthorised migrants by the millions are absorbed into America’s workforce, accounting for more than 5 per cent of all jobs, particularly in low-end construction and services. Legal limbo is the price that the migrants pay for an improvement in their lives. Insofar as they affect the labour market, it is above all other recent migrants who face competition.

As a modus vivendi this is infinitely preferable to draconian immigration enforcement. But it amounts to an abdication of regional leadership and institutionalised condescension. Central America is in effect labelled as beyond hope. This stands in sharp contrast to Washington’s bold claims about its proper role in faraway Asia. It also contrasts sharply with the visions of a better America promised by Bidenomics.

One can only hope that if Harris does win the presidency, she will embark on the kind of ambitious policy for America’s immediate neighbourhood that she was unable and unwilling to push while serving as VP.

Read the full article here