Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The writer is former chief of MI6 and UK ambassador to the UN

It is hard to understand how the Israeli drone operators failed to know that the World Central Kitchen vehicles they struck on Monday in Gaza were a humanitarian convoy. The convoy’s movements had been shared with Israeli forces and the vehicles clearly marked for a drone camera to see.

It would be a huge departure if the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) had directly targeted foreign aid workers — that is the sort of tactic the Russians and Syrians use, not a democracy like Israel with a free media. My experience from many conflict zones is that a cock-up is more likely than a conspiracy. But the attack reflects very badly on Israel’s disregard for civilian life in its pursuit of Hamas in Gaza.

The implications for Israel are severe. In human terms, the death of foreign aid workers is no greater a tragedy than the death of Palestinian civilians. But the political consequences are very different. For some months, Israel has been straining at the limits of its operating licence from its supporters, above all the US. Those limits have now been breached.

Israel has a military case for attacking the remaining Hamas battalions sheltering in Rafah. They are organised military units who pose a security threat. But Israel’s friends are baulking at continued arms supplies while the IDF operates in such a reckless manner. By allowing the IDF to overstep the rules of war in its response to Hamas’s atrocities on October 7, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu is giving Hamas a political victory.

When you are in a hole, the first step is to stop digging. After six months of conflict, the way forward now is for Israel to negotiate an end to its major operations in Gaza in return for the release of the hostages held by Hamas, and to work for a new stability in the territory without Hamas in control. That will be hard to achieve. We have learnt from Afghanistan, Iraq and Libya that when a thoroughly nasty regime is removed, the resulting chaos can be even worse than what came before. There is no authority to hold to account. Violence between factions is inevitable.

I have no confidence that this Israeli government will be able to accept an external security force in Gaza or a beefed-up UN operation to deliver essential services. But we should start planning for that now as indefinite Israeli occupation would be worse for both Israel and Palestinians in Gaza. Netanyahu’s unstated goal of an apartheid Israel — where Palestinians live in carefully controlled enclaves with no rights — has demonstrably failed.

The real threat to Israel’s existence doesn’t come from Hamas terrorism, it comes from Iran. The strike against the Iranian consulate building in Damascus this week was much more relevant to Israel’s real security needs. In what we assume was their targeting of diplomatic premises, Israel was taking a political risk. But Iran seems to have been abusing the rules that protect diplomats by allowing the building to be used as a military HQ for Quds Force commanders.

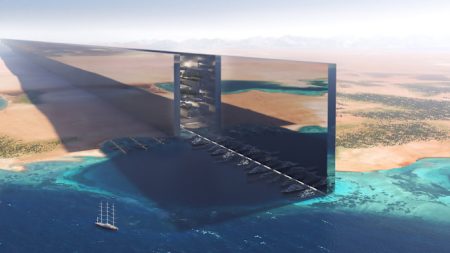

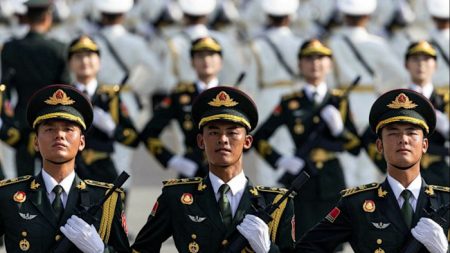

By carefully watching Tehran’s response to each twist of the current crisis — the controlled rocket exchanges across the Israel-Lebanon border, the tailing-off of Houthi strikes on Red Sea shipping, the absence of a repeat militia attack after the one that killed three American soldiers on the Jordan-Syria border — Israeli analysts will have concluded that Iran does not want to be pulled into a wider war any more than the US does. That reluctance to up the ante has encouraged Israel to go further than before in its attacks on Iranian officials.

Iran will respond to the Damascus strike. This could be inside Israel — there are already reports of a Palestinian plot against Itamar Ben-Gvir, Israel’s far-right security minister, though that was probably planned before the events of this week. An attack on an Israeli diplomatic mission abroad is also possible, like the one against the Israeli embassy in Buenos Aires in 1992.

There is now a greater chance that Israel and Iran will escalate their conflict in Lebanon. Hizbollah has a huge arsenal of rockets and missiles aimed at Israel which Netanyahu’s government would dearly like to take down. Netanyahu has so far resisted pressure within his war cabinet to open a second front in the north. He knows the White House would have little sympathy if Israel itself launched a new war, but his own calculations on how to keep himself in office seem to take precedence: a political reckoning in Israel is unlikely to take place until the fighting has ended.

For its part, Iran doesn’t want to have to re-equip Hizbollah after yet another Israeli invasion of Lebanon as they did after 1982 and 2006. But a conflict between their most capable proxy militia and Israel would be less costly in terms of stability at home than if Iran was a direct belligerent.

Hizbollah have a vote in this too. Their political position in Lebanon would be weakened by another war with Israel. But they may have little choice if Netanyahu and the Iranians opt for that course. The risks of a new conflict in Lebanon have been rising for some months and the Damascus consulate strike — however skilfully targeted and executed — has pushed the likelihood of that up further.

Read the full article here